Blog #5 - Development of the NHS Tayside Renal Supportive Care service

I’m currently in Australia, and have so far learned a lot about the development of services in New York, Pittsburgh, Tasmania and Edmonton, Canada. I will now describe the NHS Tayside service.

I continue to travel to some beautiful places in Australia and meet some inspirational people involved in Kidney Supportive care. My husband was able to join me for almost three weeks which was great as it could get quite lonely travelling from place to place. I stayed in nine different places in USA and Australia within a 4 1/2 week period of time. With constant packing and unpacking I have so far lost my hairdryer, laptop charger, travel pillow and glasses case! When Alistair arrived he did all the organisation to visit some amazing places in Tasmania, Sydney and Byron Bay. This allowed me to visit hospitals, have virtual meetings and continue to have the brain space to work on my Churchill Fellowship project. I am now in Brisbane based at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital.

Beautiful Freycinet National Park, Tasmania

Stunning Wineglass Bay, Tasmania

Our main accommodation during our time in Tasmania - cosy!

Cradle Mountain, Tasmania - it was freezing! There is snow on the mountain and we didn’t have the appropriate clothes!

In this blog I am going to describe the development of the Kidney Supportive Care service in NHS Tayside, Scotland as it can be helpful for other professionals to know how a service has evolved. The name that we have given our service is the Renal Supportive Care service. This blog will cover the following:

How and why the Renal Supportive Care service was initiated in 2007

How it evolved and was funded

Outcomes of the Renal Supportive Care service

What does the Renal Supportive Care service look like now (2024)

Warning - this blog is quite long!

In 2005, as mentioned in Blog #2, the Department of Health for England and Wales published the National Service Framework for Renal Services. It stated that people with established renal failure should receive timely evaluation of prognosis, information about the choices available to them and that for those near the end of life, there should be a jointly agreed palliative care plan built around the individual’s needs and preferences.

How the NHS Tayside Renal Supportive Care service started and evolved

1. Initiation of the NHS Tayside Conservative Care clinic:

In 2007, the clinical lead of the Renal team in NHS Tayside was Dr Iain Henderson. He prioritised funding for a clinic for patients with kidney failure who were believed too frail to start dialysis or who did not wish to start dialysis, yet still required input from the kidney team. This treatment option at the time was called ‘conservative care’ and so the clinic was called the ‘Conservative Care’ clinic. The renal consultant who took on and progressed this service was Dr Maureen Lafferty. She was keen that palliative care had involvement in the clinic. Although it was not possible for a palliative care consultant to dedicate protected time to the clinic, specialist registrars in Palliative Medicine all received blocks of non-cancer training. It was possible for time to be spent in the Conservative Care clinic and Dr Fiona McFatter was the first registrar in NHS Tayside to do this. She spent time with Dr Fliss Murtagh and specialist nurse Emma Murphy at Kings College Hospital, London. They were developing a service to meet the palliative needs of kidney patients. Fliss was also doing research at the time and looking at the symptom burden experienced by patients with kidney failure. They shared the tools that were being used for their conservative kidney management (CKM) clinic; the Palliative Care Outcome Score – renal (POS-r) and the Palliative Performance Score (PPS). These tools were introduced into the NHS Tayside Conservative Care clinic so that each patient who attended received an assessment of symptoms and performance status assessed, as well as discussions around preferred care towards the end-of-life. Patients also received routine kidney care at the clinic.

I also had the opportunity to spend time on the renal unit and in the conservative care clinic.

2. Dedicated funding from the renal service for specialist palliative care:

When I became a consultant in 2010, I was offered one session (1/2 day) per week by the renal service to provide dedicated input to the renal team. My role was to continue to work alongside Dr Lafferty in the conservative care clinic. It was, and still is, quite unusual in the UK, for another speciality to fund protected time from palliative care to deliver integrated working.

NHS Tayside is a geographically large area covering 80 x 100 square miles and is made up of four main areas – Tayside which covers Perth and Kinross, Angus and Dundee and has a population of 415,000. It also provides some care for people who live in North East Fife which has a population of 74,000. There are 27 beds in the Ninewells dialysis unit (Dundee), 12 beds in the Perth Royal Infirmary (Perth) dialysis unit and 8 beds in the Arbroath Infirmary (Angus) unit. Each area provides kidney clinics and the main in-patient unit is in Ninewells Hospital.

The Conservative Care clinic was held in Ninewells hospital, Dundee. All patients attending the clinic were known to the renal team and had chosen a non-dialysis pathway - conservative kidney management (CKM). Patients who had chosen CKM could choose to continue to attend the advanced kidney disease clinic with their normal renal consultant if they did not wish to come to the Conservative Care clinic. All patients attending the Conservative Care clinic had a joint consultation with palliative care (myself) and renal (Dr Lafferty). We checked that patients understood their treatment decision and explained that as well as routine kidney care there would be a focus on symptom management and Advance Care Planning (ACP).

Results of an audit of the conservative management clinic and expansion of service

As this was a new service, we did an audit looking at the outcome for patients seen between 2009 – 2011. During this time, 51 patients who were known to the renal team had chosen CKM. However, only 50% of the patients were seen in the Conservative Care clinic. The others were either too frail to attend or did not wish to travel to Dundee. If a patient did not attend, symptoms were not formally assessed and documented nor were ACP conversations. For the patients receiving a joint consultation at the Conservative Care clinic, symptom scores improved with time (despite disease progression) and ACP conversations were more likely to be documented.

We therefore applied to the British Kidney Patient Association (BKPA) (now known as Kidney Care UK) for three years of funding to allow a specialist nurse to work alongside us. The nurse could see patients across all clinical areas covered by NHS Tayside and could also provide community visits. The funding covered an additional session for palliative care (myself) to train the nurse in symptom management and advance care planning conversations as well as accomodate the increasing number of requests for palliative care input for the dialysis out-patients. The specialist nurse was one of the renal charge nurses, Sarah Cathcart, who had worked in a secondment post in the acute palliative care unit (APCU) within Ninewells hospital and was very keen to transfer her skills to caring for patients with kidney failure.

Development of the Renal Supportive Care service 2012 - 2015

Roles of the Renal Supportive Care team:

With the appointment of a Renal Supportive Care (RSC) nurse specialist who was able to provide care for all patients who had chosen a conservative kidney management (CKM) pathway, as well as patients who were on dialysis, the service was re- named the Renal Supportive Care service (RSC). The RSC nurse saw both CKM and dialysis patients within Ninewells as well as the satellite renal units in Perth and Angus. She provided home visits to those patients who struggled to attend clinics. A joint integrated clinic was held fortnightly in Ninewells hospital by the Palliative Care consultant, the Renal consultant and the Renal Supportive Care nurse for CKM patients who were based in Dundee and any other patient from across NHS Tayside who needed enhanced support and was able to travel to the clinic. If a CKM patient was too frail to attend clinic, the palliative care consultant could provide a home visit with the RSC nurse.

The palliative care consultant (myself) provided written or verbal advice to the RSC nurse for patients on dialysis or those who had chosen CKM and provided direct face-to-face consultation when this was required by the RSC nurse or any of the renal consultants.

The renal consultant (Dr Lafferty) provided care for her dialysis patients, provided the renal leadership for the Conservative Care clinic and provided overall strategic leadership for the Renal Supportive Care service.

Dialysis Supportive Care clinics:

On alternate fortnights a supportive care clinic was held for dialysis patients, provided by the nurse and the palliative care consultant. Any dialysis patient could be referred by any of the renal consultants or dialysis nurses as long as they met one or more of the following criteria:

Symptoms which were not controlled despite routine renal care

Patients with complex psychosocial needs requiring enhanced support

Patients struggling with dialysis and considering withdrawal.

Patients thought to be at risk of dying in the next few months

The clinic was held in Ninewells hospital with 3 monthly clinics held in Perth Royal Infirmary. During clinic time, patients could be seen in the place most appropriate for the patient - clinic, dialysis or in a community setting. All patients continued to receive routine renal care by their individual renal consultant.

Advance Care Planning:

All patients receiving consultations from the RSC service had an ACP with electronically documented conversations including resuscitation status and end of life values and preferences. These were communicated by electronic letter to the GP and primary care team, as well as other professionals involved in the patient’s care. The GP practice was requested to upload this information onto the Key Information Summary (KIS) which allows key information from a patient’s GP electronic record to be shared with healthcare professionals across Scotland, including the Scottish Ambulance Service.

Guidelines for Symptom Control and End-of-Life Care, Eductation and Multi-disciplinary (MDT) meetings:

The Renal Supportive Care team took the lead in writing guidelines for symptom control and end of life care for patients with kidney failure. These were made available on the NHS Tayside intranet so that they could be accessed by those working in primary and secondary care within NHS Tayside. Regular education sessions were delivered to the wider multiprofessional renal team about kidney supportive care and symptom control. A regular MDT was started on a 6 weekly basis, alternating between CKM patients and dialysis patients. Professionals who attended the MDT included the RSC nurse, the renal consultant leading the RSC service, the palliative care consultant, renal pharmacist, renal dietician and hospital chaplain. Additional members who attended the dialysis RSC MDT were the dialysis charge nurses from all three dialysis units and other renal consultants if available to attend at the time of the MDT.

Outcomes of the Renal Supportive Care service on CKM patients:

An observational retrospective study was done over a 30-month period to assess the impact of the funded posts on patients receiving CKM. During this time, 98 patients known to the NHS Tayside renal team had chosen conservative kidney management (CKM).

Patients receiving a RSC consultation:

71/98 (72%) CKM patients had a RSC consultation across all care settings in NHS Tayside. There was a total of 507 consultations during this time consisting of a combination of telephone call, clinic and / or home visit. 326/507 (64%) attended a RSC clinic, 35/98 (36%) received a home visit and 25/98 (26%) received a telephone consultation. Some patients received all three types of consultation.

For those patients who did not receive a RSC consultation, this was because the patient either died prior to being seen (late referral) or the renal consultant did not refer to the RSC service.

Improvement in Symptoms

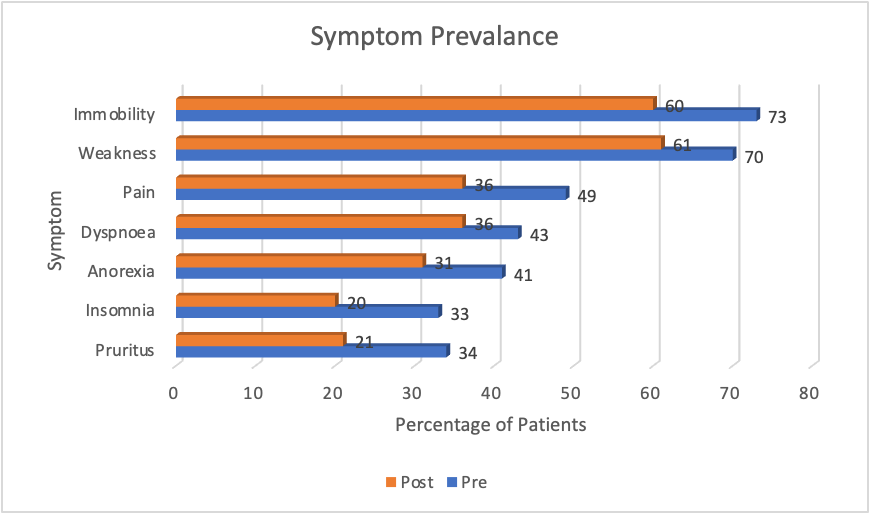

All patients who received a RSC consultation had their symptoms assessed at each consultation using the POS-renal. The symptom prevalence was consistent with previous studies (Figure 1)

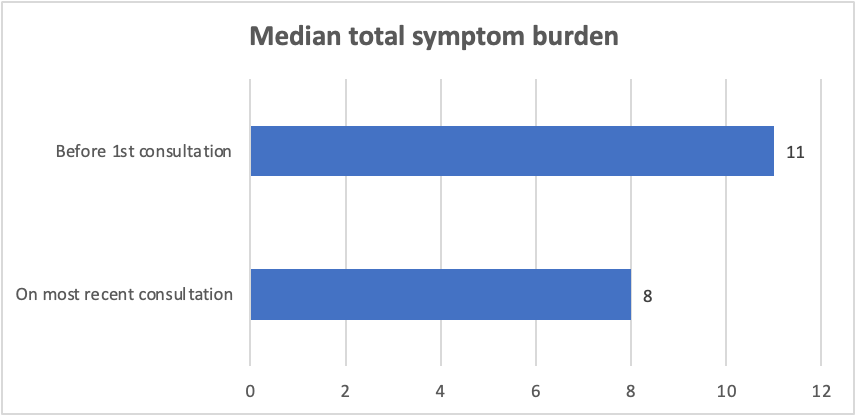

The median total symptom burden was 11 at first consultation but fell to a median score of 8 at the last consultation within the study period (p=0.03) (Figure 2)

Figure 1 - Symptom prevalence before and after RSC consultation

Figure 2 – Median total symptom burden score before and after consultation

Advance Care Planning

For those patients who received RSC input, 56/71 (79%) had an Advance Care Plan (ACP) compared to 5/27 (19%) of those who received routine kidney care only (p<0.001). The preferred place of care (PPC) at end of life was documented in 48/71 (68%) of patients receiving a RSC consultation and only 7/27 (26%) receiving routine renal care (p<0.001). Do not attempt Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNA CPR) was discussed and documented in 57/68 (84%) patients with RSC input and in 8/17 (47%) without (p<0.001).

Mortality Data

During the study period, 61/98 (62%) of the patients managed conservatively died. All patients who had an ACP had wished to have end-of-life care in a community setting (home / hospice / care home / community hospital).

10/23 (43%) of patients without an ACP died in an acute hospital versus 11/38 (29%) of patients with an ACP (p=0.25)

13/27 (48%) of patients without documentation of PPC died in acute hospitals versus 8/34 (24%) of patients with documentation (p=0.04) (Figure 3)

Figure 3 - Proportion of patients with / without an ACP who died in an acute hospital

Conclusion

Our study was not a randomized controlled trial as we were trying to demonstrate the impact of a new clinical service. The use of a retrospective cohort design, meant that we were able to demonstrate associations amongst input from the RSC team and symptom identification, symptom control and ACP communication.

By integrating renal and palliative care services, the development of the Renal Supportive Care service offered a holistic approach to conservative kidney management, placing the patient’s priorities at the centre of the care. Patients’ symptoms were more likely to be identified and improved and advance care planning more likely to be delivered, compared to if the patient received routine renal care. By being realistic and discussing inevitable decline and death, the Renal Supportive Care team played a role in helping patients achieve their preferred place of care and avoid admission to an acute hospital at the end of life.

Here is the reference for the full publication of this study. Douglas CA, Sloan J, Cathcart S et al. The British Journal of Renal Medicine 2019; Volume 24 (3):60-65

Continuation of NHS funding for the service

During the period of time that we had funding for the RSC nurse and additional funding for palliative care, we were able to show improved outcome for CKM patients and we were also providing a supportive care service to dialysis patients, as well as an educational role to the wider renal team. In addition, the number of people choosing CKM was increasing and the number of people starting dialysis was no longer rising exponentially. We cannot say exactly why this occurred, but perhaps the fact that patients were now receiving pre-dialysis education where CKM was described as an active treatment choice with significant healthcare support may have played a role.

When the three years of funding from the BKPA ended, the NHS Tayside renal team agreed to permanently fund the renal supportive care nurse without additional resource being required, perhaps due to the cost-saving of less people choosing dialysis than had been projected.

The Renal Supportive Care Service – 2024

Over the years the RSC team has expanded and has evolved due to increased workload.

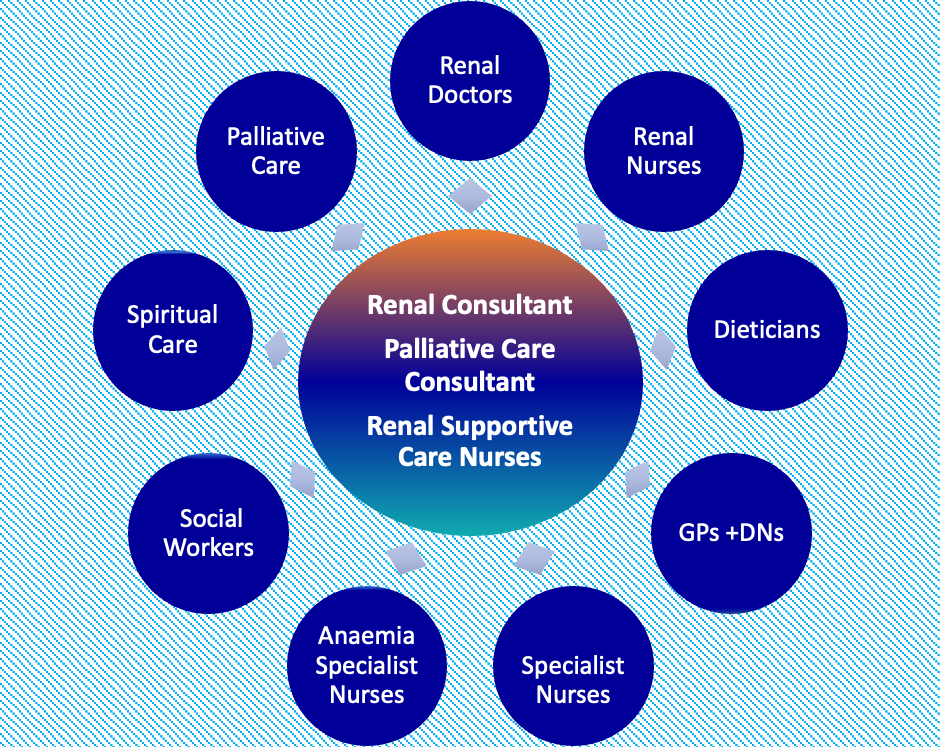

At the core of the team we still have the palliative care consultant (myself) providing one session per week and a renal consultant (Dr Lafferty) providing one session per week and Sarah Cathcart providing specialist nurse input. However, funding for specialist nursing has increased so that we have 2.6 whole-time equivalent (WTE) nurses. Our additional nurses Gill Wood and Maggie Barr provide education around treatment choices and have a role in the advanced kidney care clinics, as well as providing renal supportive care. These areas all dovetail appropriately into each other so that continuity can occur across a patient’s illness trajectory. Beyond the core team is the wider renal team, hospital and community palliative care teams and primary care teams who all provide significant care for kidney patients, with support from the RSC team when required.

The nurses and renal consultants continue to refer any renal patient to myself if additional support is required. As the renal team have developed significant expertise in ACP discussions and symptom control, I tend to only see patients who are particularly complex - often younger dialysis patients. I have admitted a dialysis patient into the palliative care unit (hospice) in which I work as symptoms were so complex and daily review was required to assess effectiveness and tolerance of treatments. During the admission, the patient was called for a kidney transplant and transferred from the hospice to the transplant unit where successful surgery was performed. This demonstrates how integrated our service has become and how palliative care is really following the Bow-Tie model.

In my next blog, I will further describe aspects of the NHS Tayside service and start to describe my learnings from USA and Australia.